Washington Trails

Association

Washington Trails

Association

Trails for everyone, forever

| by Lace Thornberg

"Because it’s there,” as George Mallory so infamously put it, is as good a reason as any to set your sights on a summit or a long-distance hiking trail.

But if you need more persuasion than simply knowing the challenge exists, here are five more reasons to give the Oregon Desert Trail a try.

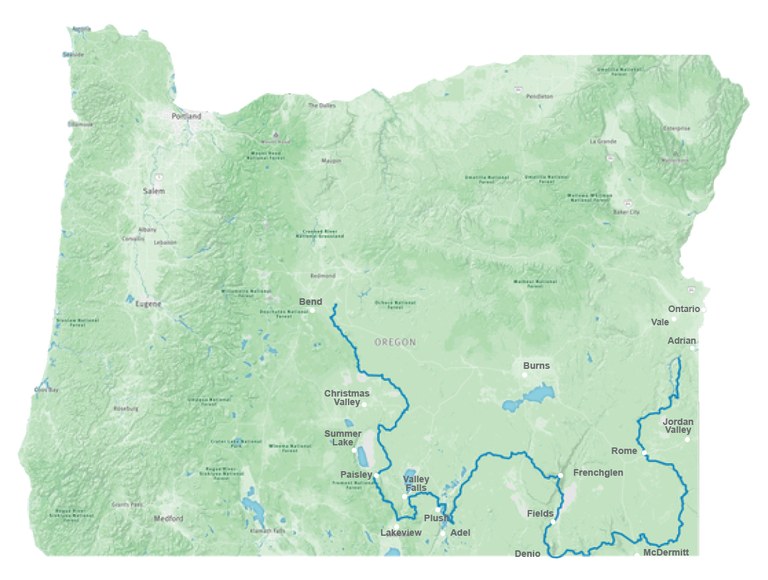

The Oregon Desert Trail carries travelers through diverse terrain as it winds from central Oregon to the Idaho border.

You’ll start in the juniper-dotted plateaus of the Oregon Badlands Wilderness. Around mile 270, you’ll travel across the lake-strewn plateaus of the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge before charging up the glacier-carved gorges on Steens Mountain. Large cairns mark the way in the Pueblo Mountains, before the route finally drops you into the stunning red rock of the Owyhee Canyonlands.

You’ll experience vistas that stretch what you know as wide open. Sapphire-blue skies, coal-black starry nights. This is sagebrush and tumbleweed country. This is the American West.

Think of the Oregon Desert Trail as a concept to be followed.

More route than trail, the Oregon Desert Trail was created by Oregon Natural Desert Association (a nonprofit dedicated to protecting and restoring Oregon’s high-desert lands and waters) to connect southeastern Oregon’s scenic highlights.

To craft this 750-mile route, ONDA stitched existing trails, old roads and even historical wagon roads together with stretches of cross-country travel through public lands and public rights-of-way.

You won’t find the same distinct path and signage that you expect from a national scenic trail like the Pacific Crest Trail or the Appalachian Trail.

Instead, ONDA provides maps, GPS waypoints and a host of other planning tools to help people follow the route as they’ve envisioned it. Exactly how to do so is up to each individual hiker — or biker, rider or rafter, for that matter.

Sections of the Oregon Desert Trail — the “ODT” as it’s known to its explorers — can also be explored on horseback, by boat, by bike or even on skis in the winter.

To make planning easier, ONDA has divided the full 750-mile route into four regions, with a total of 25 sections of 20 to 40 miles each, all of varying difficulty. Where you hop on or off is entirely up to you.

Renowned Washington hiker Heather “Anish” Anderson, who’s finished both the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail in record time, called the Oregon Desert Trail the “hardest hike I’ve ever done.”

But don’t let that scare you.

Thru-hiking the entire ODT is not for the beginning long-distance hiker, but it’s possible to choose a section that is well-matched to your skills.

Sections of the ODT in the Oregon Badlands Wilderness, Fremont National Recreation Trail, and Big Indian Gorge in the Steens Mountain Wilderness follow well-marked paths and offer easy entry points to the Oregon Desert Trail experience.

For a more demanding, but not expert-level trip, try a section along Abert Rim, through the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge or up and over Pine Mountain.

Big Indian Gorge. Photo by Michelle Alvarado

To navigate the ODT’s most difficult sections, hikers need solid navigation skills and significant outdoor experience and they need to have done some serious prep work.

As ODT coordinator Renee Patrick sees it, the ODT motivates people to build their backcountry skill set up enough to tackle the trail.

“When you can read a topo map and translate it to the features you are hiking through, a whole new world opens up,” Renee said. “I like to say that the Oregon Desert Trail is ‘a suggestion’ and I encourage hikers to make the route their own. Climb that mountain, or explore that canyon. Adjust according to your own curiosity. We want to empower people to find their own path of least — or most — resistance.”

Want to push yourself? The stretch between Christmas Valley and Paisley requires caching water ahead of time. The West Little Owyhee is a slot canyon that calls for bouldering and swimming. To descend off Steens Mountain, you’ll lose 5,000 feet of elevation over 13 miles with heavy bushwhacking.

The ODT is unique in that it was created with the conservation of public lands as its purpose.

ONDA developed this route to improve access to high-desert wonders and to inspire explorers to step up to protect and restore the public lands and waters in this region. In short, this route was designed with hikers just like you in mind.

“Your public lands are yours to explore,” Renee said.

Thanks to thousands of hours of volunteer and staff effort and generous support from donors, the ODT went from ambitious idea to a sketch on maps to “the next big thing in hiking” in just seven years — but these are still its formative days.

Only 18 people have completed the entire trail. The number of people who have completed a section of the ODT is probably lower than the number who will hike Mount Si next weekend. Tackle a part of this route now, and you’ll be among the first people in the world to do so. And, by sharing feedback on your experience, you can help shape the trail for future users.

The Oregon Desert Trail is there, and it’s waiting for you.

The Oregon Desert Trail is a remote and challenging route, physically and logistically. Thru-hiking the entire route should only be attempted by experienced long-distance hikers. To travel any part of the ODT, travelers need to be aware of the lack of cell communication, lack of water, heat and other hazards. Several stretches offer no reliable water, and water caching ahead of time is necessary. Hiking in the spring or fall, and early or late in the day, can help provide safer, more comfortable temperatures.

It is critical to read the guide descriptions in detail and seriously consider any notes on water scarcity or challenging terrain.

Photo by John Waller.

When traveling to remote parts of the Oregon Desert Trail, recent precipitation could make roads impassable, even on flat terrain. Avoid driving on wet roads as waterlogged desert soils can bog down a vehicle in mud. Gravel roads can provide better traction, but they too must be approached with caution. The nearest tow truck could be hours to days away — and prohibitively expensive.

Part of the fun of hiking the ODT is the chance to visit small Eastern Oregon towns and hamlets, like Frenchglen and Paisley. For more information about lodging options, shuttle services and where to find the most tantalizing pies, beers and prime rib, see the Trail Towns guide on ONDA’s website.

In addition to the Ten Essentials, a number of items will help hikers negotiate the unique high desert environment, such as tall gaiters and an umbrella — for portable shade as well as the occasional rain storm.

Your number one concern is staying hydrated. This means carrying lots of water, an adequate water purification system and plenty of electrolytes. Eastern Oregon is arid, and you may require extra water. Carry more water than you think you’ll need until you are certain of your body’s requirements. Water filters are recommended, as well as a way to clean the filter, since water sources can be muddy. (A bandanna or your shirt can be a helpful prefilter.) Chemical or UV water treatments can be useful, and hikers may want to treat particularly muddy water in multiple ways. Finally, your body needs salts and sugars to help you absorb water. Drink mixes offer electrolytes, while also helping mask the flavor of desert water.

Pueblo Mountains. Oregon Natural Desert Association.

Hikers are used to sticking to the trail to minimize travel impacts, but the ODT includes cross-country, off-trail travel. Here, it’s best to avoid following other footprints and to instead choose a similar bearing and walk a short distance away. In desert soils, it only takes a few hikers to establish a tread. Use this opportunity to make you route unique; just make sure to stay on public land.

Private land is marked clearly on all ODT maps. Hikers who encounter fences on their hike may wonder if they are still on public lands. (Yes.) Many high desert lands are used for grazing; these fences keep cattle where they belong. Leave any gates you encounter as you found them. Please respect the multiple uses of the desert.

All seven Leave No Trace principles apply in the desert, plus a few unique to the desert, such as avoiding walking on cryptobiotic soil crusts. Know how to avoid damaging sensitive desert terrain and respect public and private lands and you’ll be good to go. A full set of desert travel advice and more on Leave No Trace ethics can be found at the ONDA website.

Lace Thornberg worked for Washington Trails Association from 2002 to 2011. Now based in Bend, Oregon, she manages communications for the Oregon Natural Desert Association. She recalls a time when WTA’s former executive director Elizabeth Lunney told her, “You really have to see Steens Mountain.” As usual, Elizabeth was right.