Washington Trails

Association

Washington Trails

Association

Trails for everyone, forever

The Redlining Heritage Trail offers a path to understanding, strength and empowerment | By Emi Okikawa

When Diane Sugimura was 8 years old, her parents decided to move their family from Portland to Seattle. Each morning, her mother scanned the newspaper’s housing section, looking for potential homes. It was a difficult search.

After weeks of trying, they had a breakthrough. After touring a home, the family returned to the real estate office excited and ready to sign the papers. But the manager was waiting and quickly pulled the real estate agent into the back office.

The family knew immediately what was happening. After a few minutes, the manager came out and apologized.

“I’m sure you understand it isn’t about you,” he told them. “But if we sold to you, people would tell their friends and pretty soon we would be out of business. So, I’m really sorry, but we can’t sell that house to you.”

Today, Diane is a long-time Wing Luke Museum board member who, in retirement, focuses on building on the Equitable Development Initiative she created during her tenure as the City of Seattle’s director of planning and development.

After all these years, that day still weighs heavy on her mind.

“I can still hear that conversation,” she said. “I was 8 years old. I don’t remember much from when I was 8 years old, but I can remember the name of that real estate company.”

Diane Sugimura’s experience is just one of countless examples of how housing discrimination affects communities of color across the nation.

The Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience. Photo courtesy The Wing Luke Museum.

The Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience. Photo courtesy The Wing Luke Museum. One of the trailblazers in the fight for open housing was Wing Luke, namesake of the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience. He was the first Asian American Seattle city councilmember and formerly the assistant attorney general of the State of Washington.

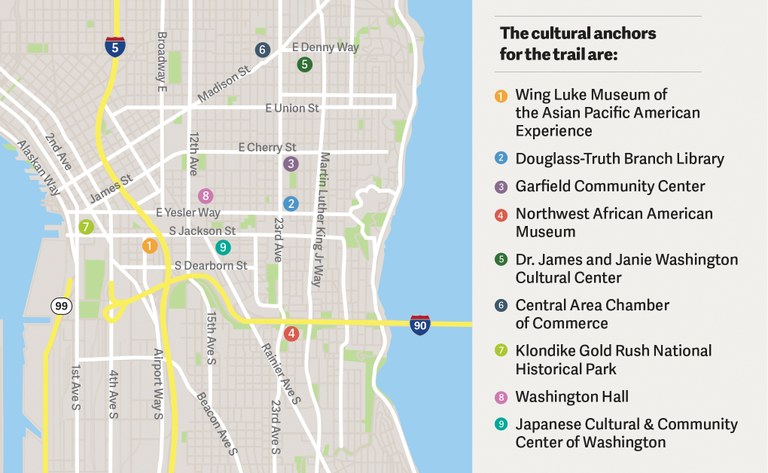

In 2018, the Wing Luke Museum was in the midst of putting together an exhibit on housing discrimination and redlining in Seattle, named “Excluded, Inside the Lines,” in tribute to Wing Luke and the upcoming 50th anniversary of the Fair Housing Act. Following the success of their first urban trail project, the Japanese American Remembrance Trail, The Wing had been looking to create another trail with the National Park Service. In addition, both The Wing and the Northwest African American Museum (NAAM) were eager for an opportunity to collaborate.

“It made sense with our history and our desire to work across communities and to build connections among other communities of color,” said Cassie Chinn, the deputy executive director of The Wing.

“We saw it as a timely, important project,” said LaNesha DeBardelaben, executive director of the NAAM. “So many of our museum members were already sharing their recollections with us of their family’s experiences with redlining. And with the rise of gentrification in contemporary times, we knew it was time for this kind of joint, community-focused project.”

The Northwest African American Museum is one of the anchors along the trail that help people learn about the history and impacts of housing discrimination. Photo courtesy Northwest African American Museum.

The Northwest African American Museum is one of the anchors along the trail that help people learn about the history and impacts of housing discrimination. Photo courtesy Northwest African American Museum.The museums decided to partner with the Park Service to create an urban trail that physically connected the two sister museums — NAAM and The Wing — to tell an important Seattle story that has impacted both of their communities.

And so, the Redlining Heritage Trail project was born.

The project pulled together 17 people for a community advisory committee. Eventually, after a year of work, the project moved into test walks. According to participants, it was difficult to narrow down which sites could fit into the trail, as they all had their own place in Seattle’s history. While the conversations were often heavy, participants found strength and empowerment through the collaborative process.

“(People) looked at developing the trail as a way that they could actively do something,” Cassie said. “You could have that sense of agency and come together as a group to do something positive in the face of all of that pressure.”

While it was difficult delving through Seattle’s shameful history of housing discrimination, community members didn’t want the story to just be about what was done to them. Rather, they focused on the experiences of people and their stories, which include examples of challenges and resilience. Through the trail, participants aimed to show that, despite having to live within the red lines, communities came together to build amazing places they called home.

“It wasn’t, ‘Oh heck, I’m just dumped here and I have to live here,’” Diane said. “It became a real community.”

The Redlining Heritage Trail, which will open this summer, is an urban hike made of many individual segments. Walkers will be able to start at each segment’s cultural anchor, where they can pick up a paper map. Trail segments vary in distance, from less than a mile to about 2 miles. As you walk, you will learn more about the communities, their rich histories and thriving present-day lives.

Just as communities across different racial and ethnic groups formed coalitions to advocate for the Fair Housing Act together, so, too, did the participants of the Redlining Heritage Trail. It was a story told by and for the impacted communities, with local resilience and power at its core.

One of the places highlighted on the trail is Yes Farm, managed by Ray Williams, managing director of the Black Farmers Collective. The farm’s mission is to hold space and fight against the displacement of African American and Black people in the Central District area.

“We don’t have to just be passive and either be forced out by rising rents or forced out by predatory lending,” Ray said. “You can actually try to stay. You don’t have to give up on the idea about having some space. But then once you have control of it, you have to make sure that it works for as many people as possible.”

Yes Farm embodies the idea that community narratives do not have to be defined by deficit and hardship. Through Yes Farm, Ray is trying to push forward with the idea that communities can pull together to create better spaces. For him, the big question is permanence.

“Sometimes, you turn the corner and it’s changed, right? Huge changes have happened. But then, how do you also create some spaces that either don’t (feel like they’ve changed) or (make you) feel that you’re a part of that change? That’s what we’re trying to do down here,” he said.

One of the big goals of the Redlining Heritage Trail is to spark conversations like these with community anchors — specific places that help tell the story of redlining.

For Diane, the walking trail is an opportunity to get outside and explore new areas of Seattle. Through the test walk, she learned more about the Central District and historically important places to the African American community.

After all, the trail isn’t just about the past — it’s also about the present. Project leaders hope that engagement will be a key part of the trail experience. Hopefully, participants will run into community leaders as they explore the trail and strike up conversations. If you happen to catch Ray out tending to his crops, you might learn about the history of the place, but also his bold plans for the future of Yes Farm and the Central District as a whole.

“Oftentimes we think, ‘Oh, we need to go down to the Elliot Bay Trail or Discovery Park’ or we need to go away as opposed to looking at neighborhoods,” Diane said.

While there is much to be gained from hiking in the remote corners of Washington state wilderness, there is value, too, in exploring the streets you travel every day. Whether your trail is rugged and unpaved, or smooth cement, there are things to learn and appreciate, right under our feet.

Cassie hopes that the Redlining Heritage Trail will provide a way for people to start thinking more about the layers of history that have happened where we stand today.

LaNesha, too, is hopeful the trail will help people to remember the proximity of the past to the present.

“We are so very close to the past and to history, chronologically and physically,” she said, “I hope people come to know the truth about James Baldwin’s quote, ‘The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.’ The trail reminds us of the presence of the past.”

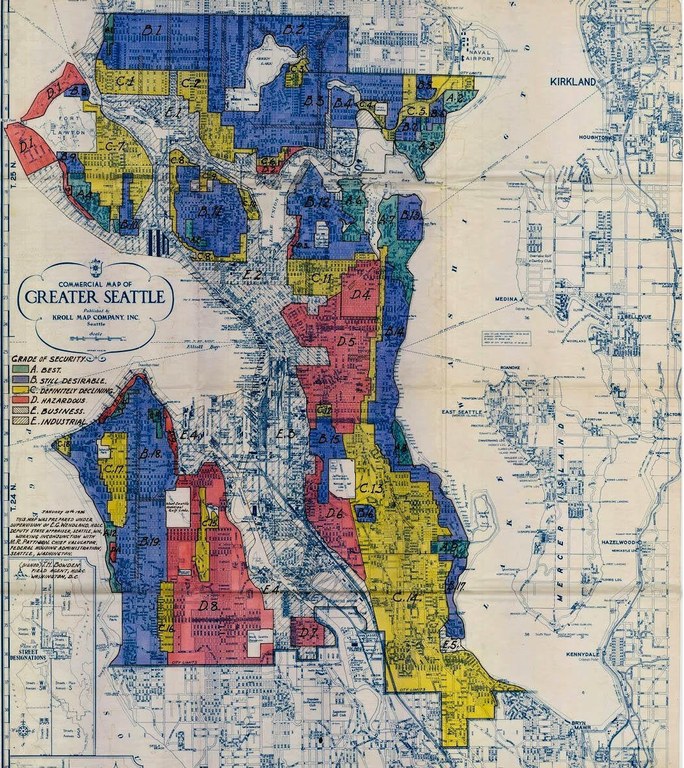

The term “redlining” traces back to the 1930s, in the midst of the Great Depression. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to prevent foreclosures and make rental housing and homeownership more affordable. In order to assess investments, the HOLC created maps based on neighborhoods’ racial compositions, deeming nonwhite neighborhoods as hazardous and coloring them red. This practice came to be known as “redlining” and federally institutionalized the discrimination of people of color — especially Black people. It perpetuated the belief that residents of color were risky investments and a threat to property values.

Racist practices like redlining and housing covenants systematically prevented individuals from marginalized communities from purchasing or renting housing. These policies robbed communities of color, primarily Black communities, of the wealth and financial stability afforded by property ownership and affordable rental housing.

While the term “redlining” is fairly modern, its ethos can be traced back to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Dawes Act of 1887. Both pieces of legislation sought to strip Native Americans of their land, sovereignty and self-determination, and left a legacy of devastating consequences. Redlining has long roots that are intertwined with our country’s very inception.

According to the Center for American Progress, the typical White household has 10 times more wealth than the typical Black household in the United States. Today, just 41% of Black households own their home, compared to 73% of White households. Here in Seattle, these federal practices paved the way for gentrification and displacement in areas like the Central District, Chinatown-International District and South Seattle — all historically communities of color.

However, there were those that pushed back against this narrative. April 11 of this year marked the 52nd anniversary of the Fair Housing Act’s passage in 1968. The act was created to prohibit residential segregation through racist practices like redlining and housing covenants and was based on the principle that every American should have an equal opportunity to seek a place to live without fear of discrimination.