Washington Trails

Association

Washington Trails

Association

Trails for everyone, forever

It’s no coincidence that King County’s Extreme Heat Mitigation Strategy was unveiled on a trail. By Linnea Johnson

In July of 2024, Washington Trails Association CEO Jaime Loucky gathered with fellow community leaders and county officials on a WTA volunteer-built trail in the sun-dappled understory of Glendale Forest, a signature project of WTA’s Trail Next Door campaign. It was a hot, sunny day, but the park’s trees provided shade and invited a gentle breeze as the group witnessed the formal launch of King County’s Extreme Heat Mitigation Strategy.

Jaime Loucky speaks at the unveiling of King County Extreme Heat Mitigation Plan at Glendale Forest. Photo courtesy of King County.

The goal of the Extreme Heat Mitigation Strategy is to reduce the harmful effects of extreme heat on the people and places in King County — and to do it equitably. It’s the county’s plan to prepare for heat events and to expand solutions that strengthen communities’ heat resilience. The strategy outlines 20 actions that King County will advance over the next 5 years in collaboration with partner agencies and organizations, including Washington Trails Association.

One of those 20 actions is “open space access,” which the strategy describes as “increasing, protecting, and maintaining accessible open space, particularly in lower income communities and identified heat islands.”

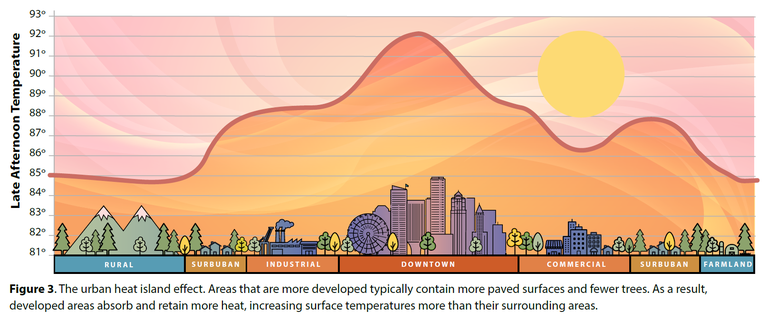

When it comes to keeping people cool, open spaces like parks, natural areas and forests are hard to beat. Whereas buildings and paved surfaces absorb and retain heat, causing a “heat island” effect, parks with trees and vegetation cool the surrounding neighborhoods and offer people immediate respite from the heat.

Figure three from the King County Extreme Heat Mitigation Plan shows how areas with more trees and green space have lower late afternoon temperatures, whereas urban heat islands retain heat later into the day.

Green spaces can help save lives — not only by bringing down neighborhood temperatures, but also by improving mental health and facilitating social connections that build more resilient communities. Well-maintained parks provide shade and the social infrastructure that make it easier for people to form bonds, increasing the likelihood that neighbors will check in on one another during heat waves.

While concerns about summer temperatures have grown with the worsening effects of climate change, it was the catastrophic Pacific Northwest Heat Dome of June 2021 that crystallized the need for decisive, concerted action. That week, Seattle reached an all-time heat record of 108 degrees Fahrenheit, shattering its record by 5 degrees. Washington state also reached its hottest temperature in recorded history: 120 degrees Fahrenheit in Hanford.

During the 2021 heat dome, 125 people across Washington died as a direct result of the heat, including 35 in King County — though hundreds more are estimated to have died of other causes that were exacerbated by heat exposure. Black and American Indian/Alaska Native residents were disproportionately more likely to visit the emergency department with heat-related illnesses.

According to the strategy, climate change made the heat dome 150 times more likely to happen and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than it would otherwise have been. As the effects of climate change intensify, extreme heat events like this one are likely to become more frequent and average summer temperatures will rise — meaning that we need to plan for “summer heat as the norm rather than the exception.”

Not everyone has equal access to lifesaving protection of parks.

“Urban green spaces are not equitably distributed. There are communities that have less access to green spaces and, as a result, experience higher temperatures. Those heat sinks tend to be in underinvested, predominantly BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and people of color] communities,” says Jaime.

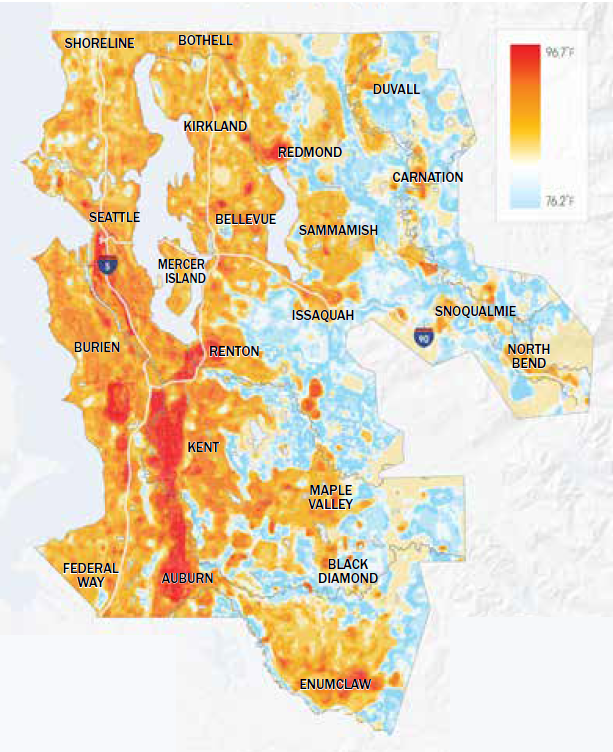

Heat islands are frequently located in areas shaped by redlining, the practice of systematically denoting non-White neighborhoods as “hazardous for investment.” Although redlining was formally banned in 1968, the strategy reports, “redlined communities to this day are still more likely to have fewer trees, less greenspace, more impervious surfaces, higher levels of pollution, and worse health outcomes.” Following national trends, King County’s heat islands are home to higher proportions of people with low incomes, seniors living alone, people with limited English proficiency, and health disparities like cardiovascular disease — and these are also the places with limited access to trees and green space.

The King County Heat Island Map shows surface temperature data collected on July 27, 2020 as part of a heat mapping campaign. People living in heat islands (shown in red) tend to have less access to the cooling effects of green spaces than those living in cooler areas, which tend to have nearby access to forests.

“Having these accessible green spaces will improve our physical, emotional, and community health, and they are important to the resiliency of our neighborhoods given the changing climate and a future of extreme weather events,” said King County Open Space Equity Cabinet in their recommendations to the King County Executive and Council.

Both the King County Extreme Heat Mitigation Strategy and WTA center equity. The county prioritizes heat mitigation projects in “heat islands, low-income neighborhoods, communities of color and other disproportionately affected communities.” WTA’s Trail Next Door campaign prioritizes urban trail projects in neighborhoods with residents who are predominantly BIPOC or low income, have high rates of environmental health disparities, or that currently lack access to green space. Advocating for investment in local parks where they are needed most is already part of our commitment to act on climate change.

Glendale Forest, the park where King County chose to launch the strategy, is one such priority trail for WTA. Located in unincorporated North Highline between highways 99 and 509 in Seattle, Glendale Forest offers open space to residents who previously did not have access to a park within walking distance. In collaboration with King County Parks, the local community and partners, our crews have been building trails at Glendale since 2020. While the park has not officially opened, it has already become a popular destination for local residents to play, explore and unwind.

Community members living near Glendale Forest, including students from Rainier Prep, a middle school less than half a mile from the park, have worked with WTA and King County on the park’s trail system since its inception. Because of its central location, the park is an ideal location for volunteers without cars, families with kids and youth volunteers to experience trail work.

Rainier Prep students joined WTA Youth trail coordinator Kaci Darsow to learn about soil ecology and trail work at Glendale Forest in 2022.

One of the three approaches King County presents in the strategy for increasing and protecting open space for heat mitigation is the acquisition of new land. The King County Land Conservation Initiative is already working toward the vision of protecting 65,000 acres of open space from development by 2050, while ensuring equitable access for all.

WTA CEO Jaime Loucky and King County Parks Director Warren Jimenez at a work party at Glendale Forest on Earth Day 2024. Photo by Victoria Obermeyer.

The strategy describes how moving forward, the Land Conservation Initiative will include heat mitigation as one of their criteria for prioritizing land acquisition. Additionally, to support efforts to cool neighborhoods, the strategy encourages land-banking, the practice of purchasing green spaces as they become available, even if resources are not yet available to build infrastructure. It’s one of the many ways this plan will improve life for King County residents for decades to come.

WTA’s knowledge and volunteer power will help supplement the county’s efforts, bringing trails to county land — and the benefits of nature to people who currently lack access to parks — sooner than if either partner were working alone.

As the effects of climate change become increasingly severe, it’s not a matter of if Washington will experience more heat waves, but when. The evidence is clear: Parks, and the trails that provide access to them, are not just a nice-to-have, but critical pieces of climate resilience infrastructure. Green spaces don’t just improve lives — they can save them. Please donate today to help WTA expand access to the essential benefits of urban green spaces.