Washington Trails

Association

Washington Trails

Association

Trails for everyone, forever

How one coordinated response to a 2021 fire in the William O Douglas Wilderness could contain the seeds for restoring and building a more climate-resilient backcountry trails system. | by Michael DeCramer

On the evening of August 4, 2021, after a long summer with record heat waves, lightning struck the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest about 20 miles west of Naches, Washington. A wildland fire ignited and grew rapidly in the dry trees and shrubs. Named after a nearby spring, Schneider Spring Fire expanded west and crossed into the William O. Douglas Wilderness. The growing blaze rushed along creek drainages and climbed up steep ridgelines, flames reaching 20 feet tall and then jumping through the crowns of trees. In places, the fire was hot enough to kill every tree it touched and burn even the organic material in the soil.

Two years after the Schneider Springs Fire. Photo by Michael DeCramer

Two years after the Schneider Springs Fire. Photo by Michael DeCramer

By the time the fire was fully contained late that fall, the Schneider Springs Fire affected an area about half the size of nearby Mount Rainier National Park. Within the fire perimeter, 75 miles of trails were impacted. The severity of the damage varies, but lost vegetation on hillsides has made slopes more vulnerable to erosion. Tree roots burned away, causing trails to collapse into small gullies. Fallen trees clogged trail corridors and blocked equestrian users.

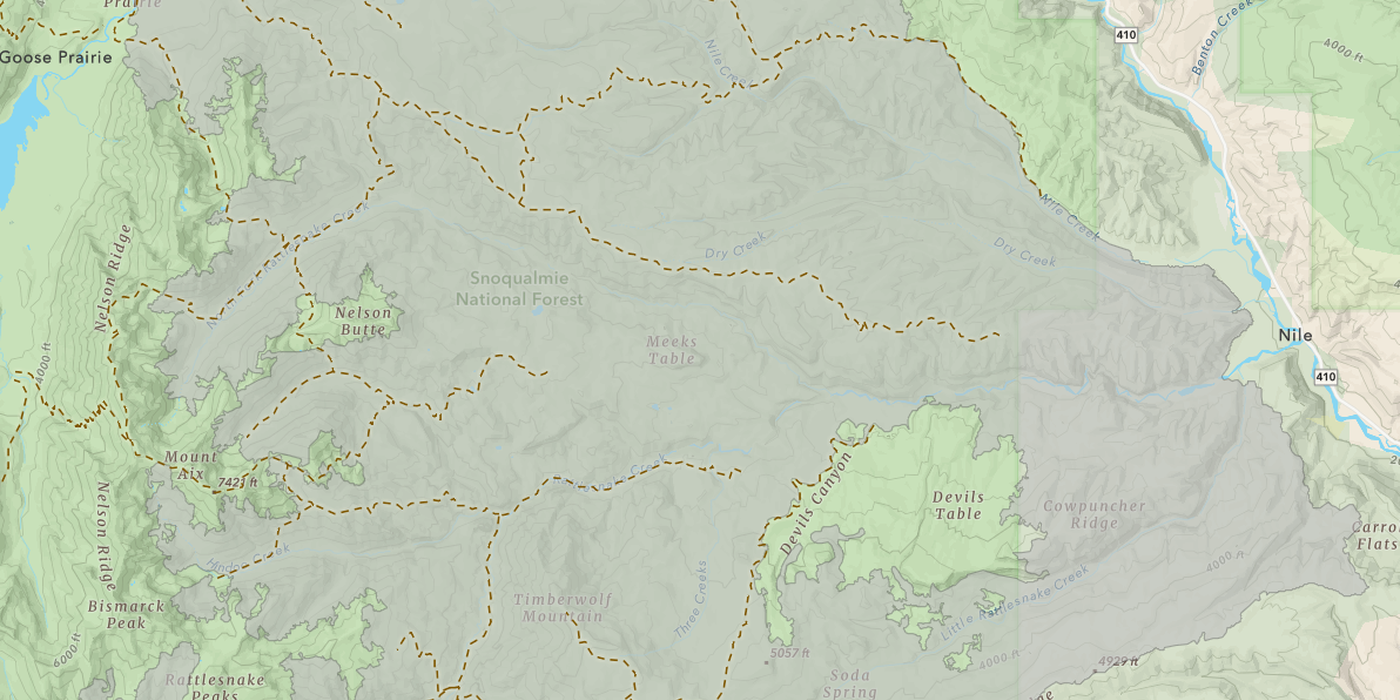

Map: The trails within the Schneider Springs fire perimeter (in grey).

Map: The trails within the Schneider Springs fire perimeter (in grey).On September 30, 2021, even as William O. Douglas Wilderness was still on fire, Congress passed a bill that President Biden signed into law providing extra funding to rehabilitate national forests burned from 2019 to 2021. Thanks to the funding in that law, the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest had extra resources to dedicate to repairing the trails impacted by the Schneider Springs Fire. This year, WTA and the Forest Service signed an agreement that put WTA crews to work helping repair trails impacted by the Schneider Springs Fire through the summer of 2025

This summer, WTA spent eight weeks rehabilitating trails in the William O. Douglas Wilderness. Crews removed 929 logs blocking trails, fixed drainage issues to prevent erosion and dug new trail tread within the 2021 fire perimeter.

WTA’s crews have extensive experience partnering with the Forest Service to address the types of conditions created by the Schneider Springs Fire. Further north on the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, WTA has been working for years to restore access to iconic areas in the Entiat River valley. In 2015, the Wolverine fire burned over 60,000 acres and damaged trails along the Entiat River drainage near Lake Chelan. In the years since the fire, WTA crews, including adult volunteer backcountry response teams, youth volunteer vacations, and paid Lost Trails Found crews, have contributed 7,671 hours of work to restore trails in the area.

Restoring trails after a big forest fire requires a multiyear commitment. It might take a decade for all of the dead standing trees to fall down after a fire. Each summer, WTA crews and our federal partners start at area trailheads. We work our way into the backcountry removing logs that have fallen over the winter, clearing brush and fixing the trail tread. The trail work season in the mountains is short, and individual sections of trails may need hundreds of hours of work. As a result, trail crews might need to work for multiple summers to improve trails sufficiently to reach the center of a large burned area.

Volunteers are critical to this work. WTA projects return to burned areas annually. Through repeated stewardship, WTA and our partner organizations have made major progress in restoring access to trails in areas impacted by large fires, like the Pasayten Wilderness. Often individual volunteers sign up for projects in a favorite area and return to work in that area summer after summer, improving conditions with each successive trip.

Volunteer work is supplemented by WTA’s Lost Trails Found (LTF) crews, composed of paid seasonal trail crew staff, who spend their summer working in the backcountry. LTF crews are focused on those places that are the hardest to reach and where the unpredictability of conditions makes it challenging to schedule volunteer projects. All types of WTA’s crews repair trails in areas where hikers might lose the ability to enjoy trails without their efforts.

WTA's Kiana Smith removing a charred log in the William O. Douglas Wilderness. Photo by Angelic Friday

WTA's Kiana Smith removing a charred log in the William O. Douglas Wilderness. Photo by Angelic Friday

The challenges of spending months working in the tough terrain of a burn are obvious. “The joys you have to really look for, but they are there, too,” said Zack Sklar, a crew leader for one of WTA’s Lost Trails Found crews in 2023. Photo by Kyvan Elep

The challenges of spending months working in the tough terrain of a burn are obvious. “The joys you have to really look for, but they are there, too,” said Zack Sklar, a crew leader for one of WTA’s Lost Trails Found crews in 2023. Photo by Kyvan Elep

Rehabilitating trails after a big fire is grueling, satisfying work.

“Something that is nice about logout is that you get to see the stark difference between when you start and when you finish, how a trail can be completely transformed,” said Lost Trails Found crew member Kiana Smith.

“The challenges are more obvious,” Zack Sklar, a crew leader for one of WTA’s Lost Trails Found crews said in early September in the final weeks of the crew’s season. The crew was camped in the William O. Douglas Wilderness near a small pond. They had spent a week clearing giant ponderosa pines with five-foot long crosscut saws and repairing eroded trails. They were in the final stretch of four months working in the blackened terrain of former forest fires. “The joys you have to really look for, but they are there, too.”

Shade is scarce and it can be difficult to find places to use as a trail crew basecamp after a fire. There are expansive views, but overhead hazards make it unsafe to camp in many areas. Earlier in the summer, Zack said the crew was working in the Entiat, which is also a burn scar and similar to Schneider Springs.

“There are areas which are not so bad and other areas where it is pretty blasted. Everything that was once a tree is just a black snag. We were out there when a big wind storm picked up. It was pretty scary, stuff started dropping all over the place and we kind of had to make a hasty retreat to our big meadow where we had made camp. Once we got there our tents were blowing sideways and all night we were hearing trees falling.”

The next day the crew hiked out to the trailhead. They counted at least 20 trees that had fallen across the trail they had just cleared overnight.

WTA crew hikes out of the William O. Douglas Wilderness at the end of a project in September. Photo by Michael DeCramer

WTA crew hikes out of the William O. Douglas Wilderness at the end of a project in September. Photo by Michael DeCramer

In an era marked by a profound lack of capacity for public land agencies, land managers appreciate WTA’s fire recovery work.

Sam Zook is the Entiat Ranger District Trails Coordinator for the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest.

“WTA’s Lost Trails Found crew has made a profound impact on the usability and condition of the trails in the Entiat Ranger District," he said, describing WTA crews’ contributions. "With over 300 miles of trails and multiple user groups, the [Forest Service’s] Entiat Trail Crew often faced challenges in maintaining these trails, especially in post-burn areas such as the Entiat portion of the Glacier Peak Wilderness. However, thanks to Lost Trail Found’s dedicated efforts and hard work over the last couple of years, the main trails in Entiat’s Wilderness have been maintained. For instance, since the Wolverine Fire in 2015, this was the first year Snow Brushy Creek Trail has been logged out to Milham Pass, thanks to the Lost Trails Found crew.”

Daisy Torres uses an axe to finish cutting a broken log to remove one of many logs blocking the Cow Creek Trail in the Entiat River Valley. Photo by Jackie Marusiak.

Daisy Torres uses an axe to finish cutting a broken log to remove one of many logs blocking the Cow Creek Trail in the Entiat River Valley. Photo by Jackie Marusiak.

The 58 miles of wilderness trails burned by the Schneider Springs Fire benefit from the hard work of WTA crews, the dedication of public servants at the Forest Service and the action taken by Congress. This year WTA crews maintained almost 23 miles of the trails burned in the William O. Douglas Wilderness, and there is more work to be done. Winter will bring down more trees. Soils loosened by the fire will wash away sections of trails. Its impacts will be visible on the landscape for decades to come. It will take many summers to recover trails across the entire wilderness and ensure that trails affected by the Schneider Springs Fire do not fall off the map. WTA staff and the Forest Service are already planning work for next year.

The frequency and severity of forest fires in Washington are expected to increase in each decade this century. Large fires like Schneider Springs will become more common as climate change increases the likelihood of hot and dry summers. As we move forward into a warmer future, the coordinated response to the Schneider Springs Fire can be a model of resilience and recovery.

In the years to come, we will need the ongoing advocacy of hikers and continued action by Congress to direct funding to repairing access to public lands. We will need the dedication and experienced skills of hardworking trail crews to face the challenges ahead. This summer in the William O. Douglas Wilderness, WTA trail crews joyfully respond to the challenges of restoring access to prominent mountain peaks and deep drainages. If we hope to keep the wonder of backcountry experiences in a future marked by fire, it will take all of us working together to keep the crews coming back year after year.